Community partnership

Towards the end of last year, I had the honour of presenting at the Association of Sign Language Interpeters (ASLI) conference, discussing themes of ‘Reframe, Refresh and Reset’. More recently, articles have been published in their quarterly magazine. You can read the previous article about empowering allyship here, or watch my presentation in BSL via the ‘Click for BSL’ tab above.

You also access a PDF version of this article here.

Philip Gerrard and Jemina Napier discuss reframing sign language interpreter training.

Over the coming decade, the landscape that interpreter training providers operate in will change dramatically. This is predominantly the result of two factors: the marked increase in the visibility of BSL and deaf people in the media (see Figure 1); and the new GCSE in BSL being offered in schools. Both of these will increase the number, diversity, and geographical spread of BSL learners.

More people will learn and be exposed to BSL from a younger age. Having BSL as a GCSE subject on a par with other traditional school subjects gives credibility to it as a language learning option (for both hearing and deaf students) and opens up career opportunities to the population, including becoming a sign language interpreter (along with other career options potentially involving BSL, such as teacher, counsellor, social worker, and so on). This will inevitably lead to greater demand for sign language interpreter (SLI) training, which means that we need to review the current training options and routes to qualification.

What kinds of programmes are needed? How should they be delivered and where? We need to ask whether what we have currently is clear, delivers quality, is a good fit to the needs of the population, and allows growth to meet increased demand. These questions need to be considered now, so we are better prepared for the upcoming change and increased demand.

What makes a good training programme?

Using MentimeterTM polls, we asked the ASLI 2024 Conference audience this question, and received a range of responses, as seen in Figure 2.

Starting at the most fundamental level, we need to assess whether the route to qualification is clear, and equivalences of qualifications and experience are well-mapped. People with an interest in working with deaf communities may be drawn to work in well-established career pathways like audiology and social work, but do they see interpreting as a potential career option?

If a careers guidance advisor is supporting a school leaver to be on the right course to achieve qualification, is the pathway comprehensible and easy to navigate, and are the pros and cons of different types of courses clearly described? If they aren’t, then this is a barrier to entry into the profession.

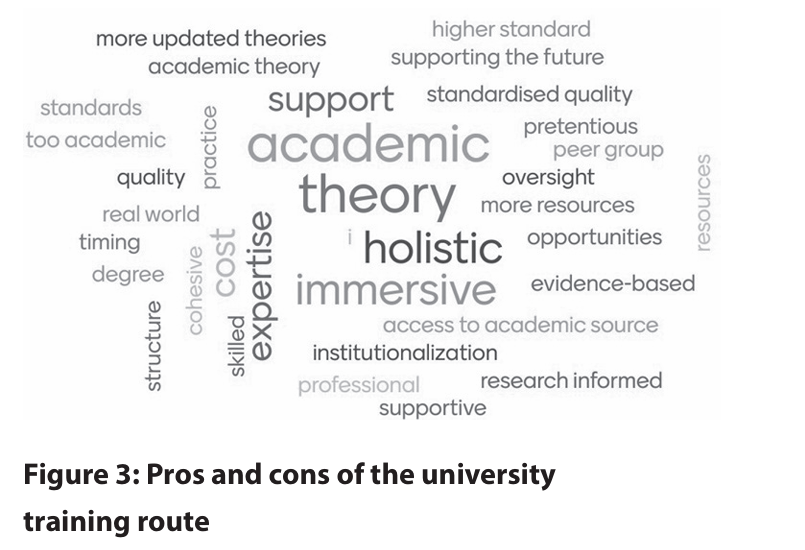

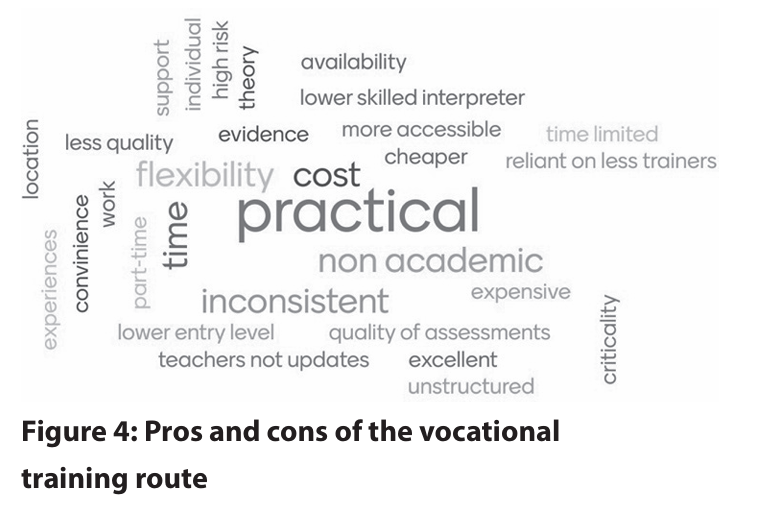

Do all the current SLI training programmes meet the criteria ASLI members want to see? Will future programmes be designed to incorporate all these requirements? Currently there are two training routes to qualification: the university route and the vocational route (through mostly private training companies). We asked the conference audience about the pros and cons of each training route, as seen in Figures 3 and 4.

The need for joined up-thinking

These training courses have been established on an ad hoc basis as the interpreting profession developed, with no strategic oversight. Although we have the National Occupational Standards, and the National Registers for Communication Professionals with Deaf and Deafblind People (NRCPD) has a process for approving training programmes that meet these standards, we feel that it is time for a review of interpreting training providers, alongside the demographics of British deaf communities – on similar lines to the mapping which produced the NHS workforce plan.

This identified the number of doctors that needed to be trained, and the locations which need more health support, to ensure equity of access. Similarly, we should ensure that the right number of interpreters are trained and qualified to work in the areas where there is the most need.

What kinds of courses do we need and where? What are the risks to the current routes? It is not just about the number of interpreters; it is about quality too. We need a closer analysis of the current pathways: and we also need to look at the reasons why some courses have not stood the test of time, in order to learn what is in fact a successful model.

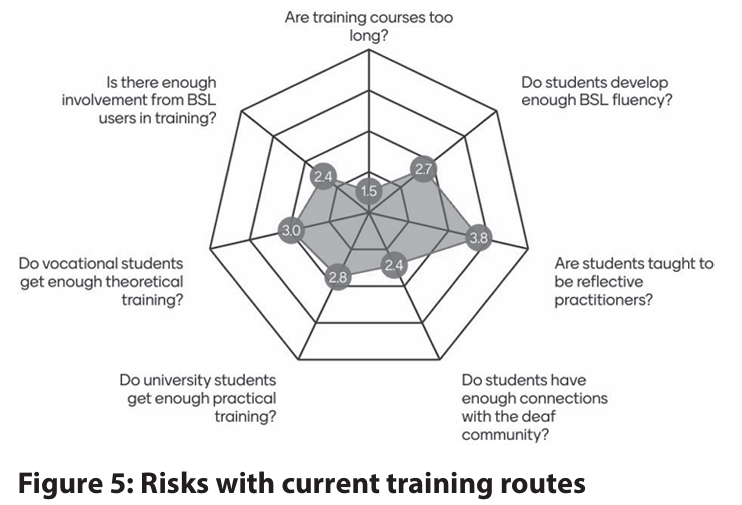

When we asked the conference audience about the risks with the current training routes, they felt that the biggest ones relate to whether vocational courses provide enough theoretical training, and whether any course sufficiently teaches students to be reflective practitioners, as seen in Figure 5.

What we need is the ‘recipe’ for producing the highest-quality interpreters for the community. The ingredients for this recipe could include the length of training courses; pre-course entry English and BSL language fluency; reflective practice teaching; the balance between practical skills and theoretical knowledge; community immersion; and the involvement of deaf and deafblind people in teaching.

The current recipe course that providers use might need to change to reflect the students of the future who already have a BSL GCSE qualification. Most importantly, we feel the most important thing that is missing in the current training landscape and SLI training is connection between training programmes and deaf communities throughout the UK.

A collaborative model

We believe that what is needed is a collaborative approach to interpreter training, as opposed to operating in a competitive market. This would allow a network of educators to be established to share good practice.

One model of training that has developed in Edinburgh between Heriot-Watt University (HWU) and the deaf community charity organisation Deaf Action acknowledges the symbiotic relationship that exists. Deaf communities need good interpreters; and, if they are to produce good interpreters, training providers need deaf communities. There is always a risk that deaf communities will feel overwhelmed by the need students place on them. By engaging through deaf organisations, this demand can be managed and the experience and exposure the students need can be used to the benefit of deaf communities.

A Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between HWU and Deaf Action established a formal framework to coordinate efforts and to reduce, wherever possible, duplicating services and resources in the achievement of common objectives.

The goal of the MoU is to work together to ensure the SLI training, and the SLI graduates, are of the highest standard. An action plan was developed to monitor the partnership’s achievements so that tangible benefits to each party can be demonstrated, and a working group meets quarterly to monitor progress.

Deaf Action offers HWU:

- Service learning project opportunities to second-year students; they come into the Deaf Action building for a timetabled class each week over a semester and are given a project to complete on behalf of the organisation. One group, for example, mapped out a Edinburgh Deaf Heritage Tour.

- Community placements for third-year students in which students work full-time for one semester in the organisation in various non-interpreting roles (in reception, on project work, in the bar, organising events and so on).

- Interpreter shadowing placements for fourth-year students.

- Volunteer opportunities for Deaf Action at events such as the Edinburgh Deaf Festival (see Newsli 131).

In return, Deaf Action staff are offered secondments to HWU (for example, to work on the local BSL plan), and are involved in the training programme through delivering guest lectures, being involved in role-plays and also on the final exit viva assessment panel. HWU also involves Deaf Action in considering the current and future research agenda.

By working in partnership, future interpreters and deaf communities reap benefits. The risk of duplication between the organisations is reduced by working together and as a result more resources are available to be used in a variety of ways. The students receive as close to an immersion experience as possible during their training, thereby enhancing their BSL linguistic and cultural knowledge.

Deaf people form relationships with future interpreters, reducing the stress that an unfamiliar interpreter being booked can cause. The students and graduates feel that Deaf Action is a familiar safe space. Because they are required to come into the building for part of their course, it removes the apprehension of walking into a deaf space for the first time. That means they become comfortable applying for jobs within the charity whether they pursue an interpreting career or not, and also continue socialising in the deaf community after their course has ended.

As a result of this collaborative partnership, deaf people now have a wider range of activities and events accessible to them. This includes the BSL Parkrun, BSL karaoke, BSL film club, BSL (interpreted) quizzes and BSL book club. The book club, which started three years ago with one deaf person and three HWU students attending, now has an average of 15 attendees, about 75 per cent of whom are deaf.

Events like these also attract a wider, more diverse, group of people, which means that the hearing attendees’ social interactions within the deaf community are widened. They become similar to the interactions that go on within the hearing community – after all, people go to a book club because they enjoy books, and at the club they meet other people of different ages and backgrounds who also enjoy books. It makes the deaf community less insular and encourages participation as it is not just the traditional deaf club social evening.

The partnership developed between HWU and Deaf Action demonstrates one way of bringing the deaf community and interpreting training providers closer together. Through this closeness, the needs of both will be more intuitively met than if the work is done in isolation or on an ad hoc basis.

A close working relationship between deaf communities and SLI training providers, alongside strategic and collaborative thinking, will make it possible to prepare the landscape for the changes that we need if sufficient numbers of good-quality interpreters are to be trained to meet the demand of deaf communities.

Responsibilities and making it happen

So, who is responsible for leading on the joined-up thinking that we need to: review the landscape; anticipate and plan for what training programmes are needed; and ensure that a community-collaborative model is embedded in current and future training programmes? The many key stakeholder organisations include:

- ASLI and the Deaf Interpreters’ Network (DIN)

- Interpreters of Colour Network (IOCN)

- Visual Language Professionals (VLP)

- NRCPD Signature Association of BSL Tutors and Assessors (ABSLTA)

- Black Deaf UK (BDUK)

Which of these organisations needs to take responsibility? We suggest that one organisation could lead, but working in collaboration with all the other organisations, as well as deaf community charity organisations throughout the country like Deaf Action.

In addition, Napier et al. (2022) conducted a census of the SLI and translator profession in the UK on behalf of ASLI and established that there is a clear need for more diversity and representation in the profession. The report (Napier, et al., 2021) gave 20 recommendations over five categories, with one category looking at the training/ education of sign language translators and interpreters. Within this category there are two relevant specific recommendations:

- A new network of Sign Language Interpreters and Translator Educators (SLITE) to share teaching practices, activities and materials that foreground intersectional characteristics.

- A needs analysis conducted by SLITE of vocational and academic pathways, looking at whether more and/or different programmes of which kind are needed (for example, for deaf practitioners or for working with deafblind people) and whether the current qualification pathways are fit for purpose.

We would add that there also needs to be:

- A needs analysis of vocational and academic pathways and whether more and/or different programmes of which kind are needed where, and how; and how these programmes can take into account that future students will be more ‘BSL-ready’ after the GCSE takes hold.

- Encouragement of collaborative models for the training provider-deaf community organisation partnership.

We look forward to seeing this happen, and to collaborating on this initiative. We have presented what we think are the key ingredients (deaf communities and deaf organisations, universities and training programmes and students) who should work together, as well as the recipe. Who now is going to initiate baking the cake?

Discover other CEO blog posts here.